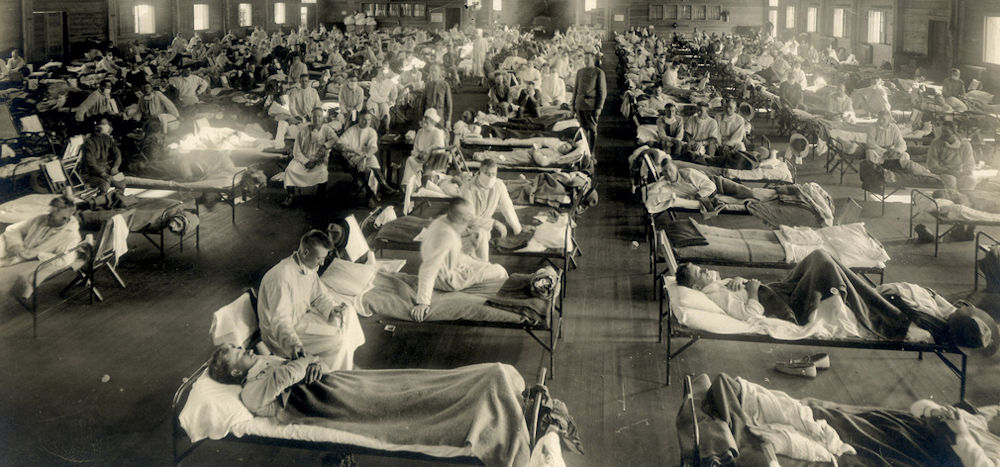

Soldiers with the Spanish flu at an American army hospital. wikipedia image.

By Warren Nunn

As the threat to humanity of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) has been revealed, some comparisons have been made to the Spanish flu outbreak a century ago.

The following is only meant to review what one person wrote at the time about the disease.

An unnamed author presented an in-depth and interesting overview of the Spanish flu and how disease spread as then understood.

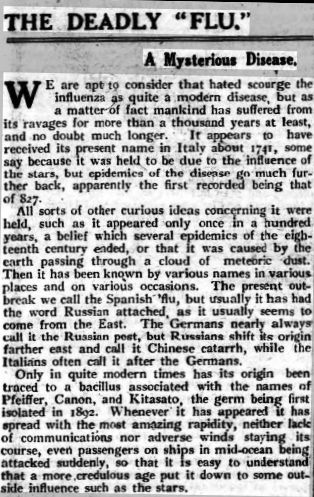

The article was published in an English paper, the Sheffield Weekly Telegraph on 23 November 1918, under the title of The deadly “flu.” A Mysterious Disease.

It started:

We are apt to consider that hated scourge the influenza as quite a modern disease, but as a matter of fact mankind has suffered from its ravages for more than a thousand years at least, and no doubt much longer.

And continued:

It appears to have received its present name in Italy about 1741, some say because it was held to be due to the influence of the stars, but epidemics of the disease go much further back, apparently the first recorded being that of 827.

It’s apparent the author either had some medical/scientific background or was a journalist who thoroughly researched the subject.

Scientists give better understanding

He then refers to some of the “understanding” about the disease’s origins.

All sorts of other curious ideas concerning it were held, such as it appeared only once in a hundred years, a belief which several epidemics of the eighteenth century ended, or that it was caused by the earth passing through a cloud of meteoric dust.

We’re then told about the names by which the disease was known.

The present outbreak we call the Spanish ‘flu, but usually it has had the word Russian attached, as it usually seems to come from the East.

The Germans nearly always called it the Russian pest, but Russians shift its origin farther east and call it Chinese catarrh, while the Italians often call if after the Germans.

The author then switches to a better understanding of how diseases are spread and mentions three scientists including Kitasato Shibasaburo, the Japanese physician and bacteriologist who helped prevent tetanus and diphtheria.

Only in quite modern times has its origin been traced to a bacillus associated with the names of Pfeiffer, Canon, and Kitasato, the germ being first isolated in 1892.

This is where his description of the Spanish flu starts to parallel the present Coronavirus pandemic:

Excerpt of Spanish flu article from Sheffield Weekly Telegraph.

Whenever it has appeared it has spread with the most amazing rapidity, neither lack of

communications nor adverse winds staying its course, even passengers on ships in mid-ocean being attacked suddenly, so that it is easy to understand that a more credulous age put it down to some outside influence such as the stars.

Any connection to the weather?

He then reveals a connection between foggy weather and disease spread, particularly in France:

Dense fog has been an accompaniment to many bad outbreaks, but whether it had anything to do with its virulence is certainly doubtful, as the epidemic during this past summer occurred during the finest weather.

It may have been a coincidence, but several visitations did occur after or during such weather.

We are told that in the spring of 1733 thick fogs, “more dense than the darkness of Egypt,” [This is a reference to the plagues we read of in the Bible (Exodus 10) that affected Egypt] prevailed in France, and always immediately afterwards influenza appeared in deadly form.

He goes on to observe a similar situation in Scotland and England:

The same phenomenon appeared in Scotland the same year, the outbreak being coincident with “a continual dark fog, the sun being seldom seen,” while in 1782 during an epidemic “the sun was, for many weeks, obscured by a dry fog, and appeared as through a common mist.”

The same thing took place in 1837, when fog and ‘flu both afflicted London together.

Insect swarms a coincidence?

Then there is reference to an insect swarm:

The weather no doubt has a great influence on the scourge, and it is said that on some occasions when it was most prevalent it was accompanied by “prodigious swarms of insects.”

The disease also affected animals, he wrote:

Animals are also liable to attacks of the disease, especially horses and dogs, which suffered severely during outbreaks in 1728, 1732, and 1775.

It appears to be particularly partial to France, where outbreaks have been numerous and severe.

The country suffered especially in 1311 and 1402, while in 1557 influenza ravaged not only France, but pretty well the whole of the world, first appearing in Asia, thence spreading over Europe, and finally appearing in North America.

An electron micrograph showing recreated 1918 influenza virions. wikipedia image.

He also refers to previous influenza epidemics:

Up to the eighteenth century epidemics which have been more or less determined as influenza did not occur perhaps more than every hundred years or so, but the reason no doubt is that so many other more virulent pests broke out from time to time that influenza was hardly deemed worthy of mention.

For about the past two hundred years its visitations have been comparatively frequent, until nowadays we regard it as a more or less regular disease of winter with occasional serious outbreaks at other times of the year.

In 1847 it was especially bad, at least a quarter of a million sufferers being treated in London, but in more modern times the great outbreak which started in 1889 in most noteworthy.

It was first announced in Russia in October of that year, and thence spread all over Europe and America, lasting off and on for some five or six years, but gradually abating in violence.

Disease spread and vigilance

It can be observed both from this 1918 description of Spanish flu and our current pandemic, that such events have happened before and can happen again.

We are in a much better position today to deal with a pandemic, but it requires everyone to be vigilant and follow* government recommendations.

The restrictions could become even more draconian should this virus continue to spread where you live.

*UPDATE June 2021. Because of the changing understanding of this virus and what works in restricting its spread, more people are challenging government recommendations.

Has my view changed?

I’m now not as comfortable with the decisions that some governments are making and that all depends on how the virus has impacted particular areas.

In Queensland, Australia, we have had very few cases compared with the rest of the nation and little community spread.

An easy, clear explanation is that we don’t have the high density living that Sydney and Melbourne have. Melbourne, of course, has had the biggest challenge with containing the outbreak.

Still, Australia has not been as badly affected as elsewhere which can be put down to a combination of community co-operation and stringent lockdown procedures to stem any potential outbreak.

With vaccinations now available, the question turns to the science and ethics behind producing them. There are also unknowns about any possible long-term effects which causes me to take a sceptical approach.

For the moment, even though I’m more susceptible to the virus being 60-plus, I’m choosing not to have a jab.

Recent Comments